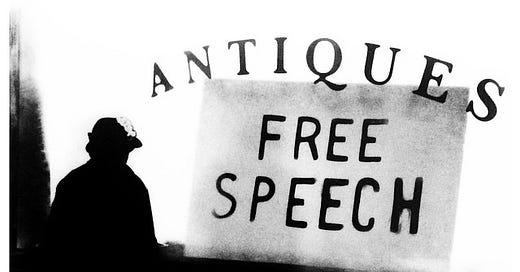

Why Free Speech No Longer Works

Another system designed for a previous era is failing us today.

Donald Trump and Elon Musk are attacking free speech. Trump is suing Iowa pollster Ann Selzer and recently won a settlement against ABC. Musk’s Twitter acquisition as a self-described “free speech absolutist” has led to a muddier information ecosystem. In a vacuum, they might be blamed as evil villains acting alone to make the world worse.

But we don’t live in a vacuum. Instead we live in a complex seascape of a world, in which the diffuse influences of many interconnected actors deserve both blame and credit for nearly everything. In such a world, it is important to identify factors that significantly affect the world, especially those we ourselves are responsible for. One of these factors, I believe, is our defense of “freedom of speech.”

This defense prevents the government from presiding over matters of truth, leaving it up to corporations who are more interested in engagement and profits than truth. Just last week, Meta announced that it would stop fact checking content on Facebook, under the influence of Trump and Musk. Meta’s Chief of Global Affairs said, “I think Elon has played an incredibly important role in moving the debate and getting people refocused on free expression.”

By rallying under the banner of “freedom of speech,” we Americans tie the hands of our government, leaving the wealthy to define the limits of permissible expression. These corporations and oligarchs, driven by profit and engagement, create an information ecosystem shaped more by their short-term interests than the public good.

It’s time for us to rethink our reverence for the First Amendment and recognize that new solutions are needed for a new era. As we did in my post on American support for individualism, let’s explore American support for free speech and how it holds us back from building a well-functioning society.

A cultural blind spot

For good reason, Americans want to protect dissent. Dissent is a key type of speech that should always be protected because we want our system to be self-critical. Self-critical systems can adapt well to new information. Think of the scientific process, which is rife with examples of paradigm shifts, as new ideas challenged old dominant views. Democratic systems also often allow dissent and therefore change. However, some areas of democracies can become overly protected from self-criticism, like American free speech.

If we are not criticizing the concept of free speech, it becomes a blind spot. Imagine trying to solve a difficult puzzle without noticing that one of the pieces is adjustable. You might push the other pieces around, turning them back and forth, making no progress in confusion. This is what it’s like trying to improve our American discourse without using the power of government. We might try to improve information literacy. We might try to Like and retweet the right posts, pushing against the ocean of disinformation. All the while, we give very little thought to how government policies can help.

Other countries are less wedded to freedom of speech. The EU has already acknowledged the problems of disinformation and created the Digital Services Act, which requires very large online platforms to identify and mitigate risks associated with disinformation. This means companies like Facebook must consider (and be transparent about) how disinformation can impact elections, public health, and societal polarization.

While the Digital Services Act is a good step and a definite improvement compared to the US’s lack of regulation, I still don’t think it goes far enough. It requires companies to perform these risk calculations, but companies do not have long-term goals in mind. They do not have the public interest in mind. They change too quickly (in leadership and focus) to be reliable shepherds of our information ecosystem, as evidenced by Meta’s change of heart. Ultimately, the government should take on this role.

Fear of government control

Of course there are good reasons for people to fear this. Governments have a tendency to grab power, and unlike corporations, they have the force of law and military behind them. Dictatorships and oppressive regimes around the world already crack down on dissent. Orwell’s 1984 warns strongly against creating the Ministry of Truth.

But just because government control of disinformation can turn dystopian doesn’t mean that it will. As an example, the human body has an extreme mass surveillance system, which requires each individual cell to be checked for the proteins it is producing. Any cell that displays the wrong proteins or doesn’t display anything is killed. This surveillance system is a huge energetic expense for the body, yet it is necessary for the prevention of cancer, which is even more dangerous than oppression of individual cell rights. And the fact that this expensive system has been preserved by evolution shows that it is indeed beneficial for long-term survival.

Societies are obviously not the same as bodies, but we constantly make trade-offs between social safety and individual rights, many of which are reasonable. The US already has mass surveillance digital surveillance, yet reasonable dissent has not been stifled by the government. The UK has a mass network of CCTV cameras, reminiscent of 1984’s Big Brother, but their citizens are largely accepting of the surveillance because it improves public safety. Such large-scale government interventions can be mitigated against overreach by court-mediated checks and mandatory transparency.

It is possible to increase government control without creating the slippery slope toward dystopia and collapse. It is also possible that government control is exactly what we need to avert the slippery slope.

Non-government control is worse

If we don’t use the government to define the bounds of acceptable speech, then we leave it up to forces that don’t prioritize the public good. Media corporations will control disinformation only if it harms their profits. The wealthy will bring civil lawsuits to restrict speech they don’t like, like Trump is doing against ABC and The Des Moines Register. Social media users will try to ratio, cancel, and shout down the voices they don’t like, which is often done in a well-meaning but short-sighted way, as discussed in my post on democracy or Robert Wright’s post on mindfully resisting Trump.

Are these anti-disinformation mechanisms better than what the government could do? The answer isn’t clear because we are too afraid to try. We pay too much attention to the risk of government overreach, and not enough attention to the risk of government underreach. We are experiencing the consequences of that risk right now, largely due to our historical roots.

Seascapes gonna seascape

In the past, social truth was determined by authoritarian regimes, who were extremely self-interested. Under English law, criticizing the government was a crime called seditious libel. The objective truth of a statement was not a valid defense under libel law. While this law might have been helpful for short-term stability, it was clearly problematic for a society trying to navigate a changing world.

So when Americans won independence, they chose to limit the powers of the federal government using the Bill of Rights, including the First Amendment:

“Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech.”

This moved the power of truth determination from monarchs to the people. As discussed in the post on democracy, it was a major advancement which was appropriate for that time, 249 years ago.

We are now in a different time. Voters are less well-suited to determining truth than they were. Technology has allowed disinformation to spread and take hold at scales and speeds the founding fathers could not have envisioned.

At the same time, we have developed other technologies, such as peer-reviewed research journals, which draw from deepening wells of expertise and are much better at determining truth than any system we had before. We also have innovated new forms of transparency, independent fact-checking organizations, and AI-driven disinformation detection. By clinging to a 249-year-old phrase, we choose not to use these recently developed tools, ignoring another change in the seascape. At our peril, of course.

Reevaluating our principles

Rather than rallying under an outdated banner, let’s think about what we actually want in our information ecosystem. When most people think of freedom of speech, they think of freedom of dissent, as our Founding Fathers wanted. This is something that can and should be preserved because self-criticism is good for systems and is a major feature of any search for truth.

We also want an information ecosystem that contains more truth and less falsehood, don’t we? We want to be able to turn on our kitchen faucets and have clean water flow out, free of toxins. Likewise, it would be better to have government standards that ensure the content we imbibe is clean, instead of expecting every single person to check everything they read with their “information literacy.” This is even more true now than ever, as this water is flowing into our brains faster, with no signs of slowing down.

There will always be tension between allowing dissent and filtering disinformation. Right now, we lean way toward the side of allowing dissent, filtering out almost no disinformation, thanks to our constant support of “freedom of speech,” that blunt tool from a previous era.

What if we update our refrain? We could instead rally behind “freedom of reasonable dissent,” a more nuanced principle that prioritizes self-criticism while filtering out harmful disinformation. Our policies might then bend toward a more tenable position. We might be more able to intelligently design our filters, rather than assuming that all filters are bad and making space for bad actors to place their own. The design of these filters would be done more clearly in view of the public, instead of in corporate boardrooms. And the word “reasonable,” while bound to be contentious, is already widely used in our legal system, as in the phrase “beyond a reasonable doubt.” When necessary, experts and judges could weigh in on matters of reasonableness.

To see how this might work, let’s look at air pollution as an analogy to disinformation. Companies are not free to spew out toxic fumes, even if harms are diffuse. The Environmental Protection Agency uses scientific expertise and public input to decide when emissions are too harmful. Producers who violate these emissions standards can be held accountable, while those who find rules too restrictive can challenge them in court. This system gives both public and private interests a say.

In other words, because we Americans don’t have a widely-parroted phrase like “freedom to produce” constraining our laws, we are able to balance between production and pollution. We can argue about where that balance falls and about which side has too much power, but at least there are clear mechanisms in place for public and private interests to have their say.

Not so with the diffuse harms of disinformation. We have an informational Wild West, where the powerful ride around with their band of outlawyers, preventing speech they don’t like. Meanwhile, Americans cry out “freedom of speech!” preferring anarchy over reasonable law and order. If we instead cried out “freedom of reasonable dissent,” we might be more willing to impose legal restraints on unreasonable speech and begin cleaning our informational environment. We can still hold onto our values while evolving to meet the challenges of our time. And we can stop giving cover to bad actors in the world.

Challenging the dogma

When Elon fanboys cheer his “free speech” policies at X/Twitter, they draw upon our communal reverence for “freedom of speech.” What if that reverence weren’t there? Then we could call out the unreasonableness of content on that platform and legally require changes to it. We could finally do something about the informational pollution that diffusely affects us all. And we wouldn’t leave it up to people like Trump and Musk to decide where to draw the lines.

This may end up requiring a Constitutional amendment because “freedom of speech” is enshrined in the First Amendment. Such an amendment will be very hard to pass, especially if we continue to deeply revere the term rather than seeing it for the overbroad statement it really is. Despite the difficulty, it would be worth amending to “freedom of reasonable dissent” because the current refrain is keeping us restrained.

The dogma of “free speech” runs deep, and I’m sure you have qualms about moving away from it. So let’s hear your reasonable dissent—click the comment button below and share your thoughts!

Note for my next post: My next post will discuss this video, so watch it now if you have time. Then notice how often the prisoner’s dilemma shows up in your personal relationships and in the political world.